The Fight for Indigenous Identity Through Land, History, and Food

By Sean Sherman - The Sioux Chef

This fight is far from over…

When I first began diving into Indigenous food systems, I thought I was simply reconnecting with the flavors, techniques, and knowledge that had been suppressed by the violent and racist history of colonization in America.

But the deeper I went, the more I realized that the story of Indigenous food is inseparable from the story of land theft. To truly understand our food, we must understand why it’s been so seemingly scarce, and the history that forced that scarcity into being.

As I watch political leaders in today’s world attempt to roll back decades of progress with DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) programs, while demonizing people of color to protect their fragile egos, I’m reminded of just how important it is to keep telling the true histories that shaped this country. You can try and hide or manipulate histories, but they will always be there and America completely sucks at telling its own true story.

This week, I found myself going deeper into the rabbit hole of the origins of government sanctioned Indigenous land theft. Of course, it starts earlier than America as a concept, with the Doctrine of Discovery (1452–1493), which were a series of papal decrees authorizing the seizure of “non-Christian” lands, the enslavement of Indigenous peoples, and the justification of colonization in general.

The United States government has never really been a friend to our Indigenous communities historically. For the U.S., this ideology of white supremacy in land ownership was embedded into law with the 1823 Supreme Court decision Johnson v. M’Intosh, which ruled that Indigenous peoples never held true ownership of their land. This case leaned heavily on the ideology of the Doctrine of Discovery and laid the legal foundation for justifying centuries of stolen land. It’s a ruling that still stands today, and something we must challenge. That’s a fight for another day (but soon).

Right now, I’m focused on where I live and work: Minnesota. This place is layered in colonial history, especially from the mid-1800s. Around this time, many of the state’s most recognizable names etched into street signs, counties, parks, and buildings belonged to men who profited most from dubious and violent land acquisitions.

Let’s start with one group in particular, The Knights of The Forest:

The Knights of the Forest: Minnesota’s First Hate Group

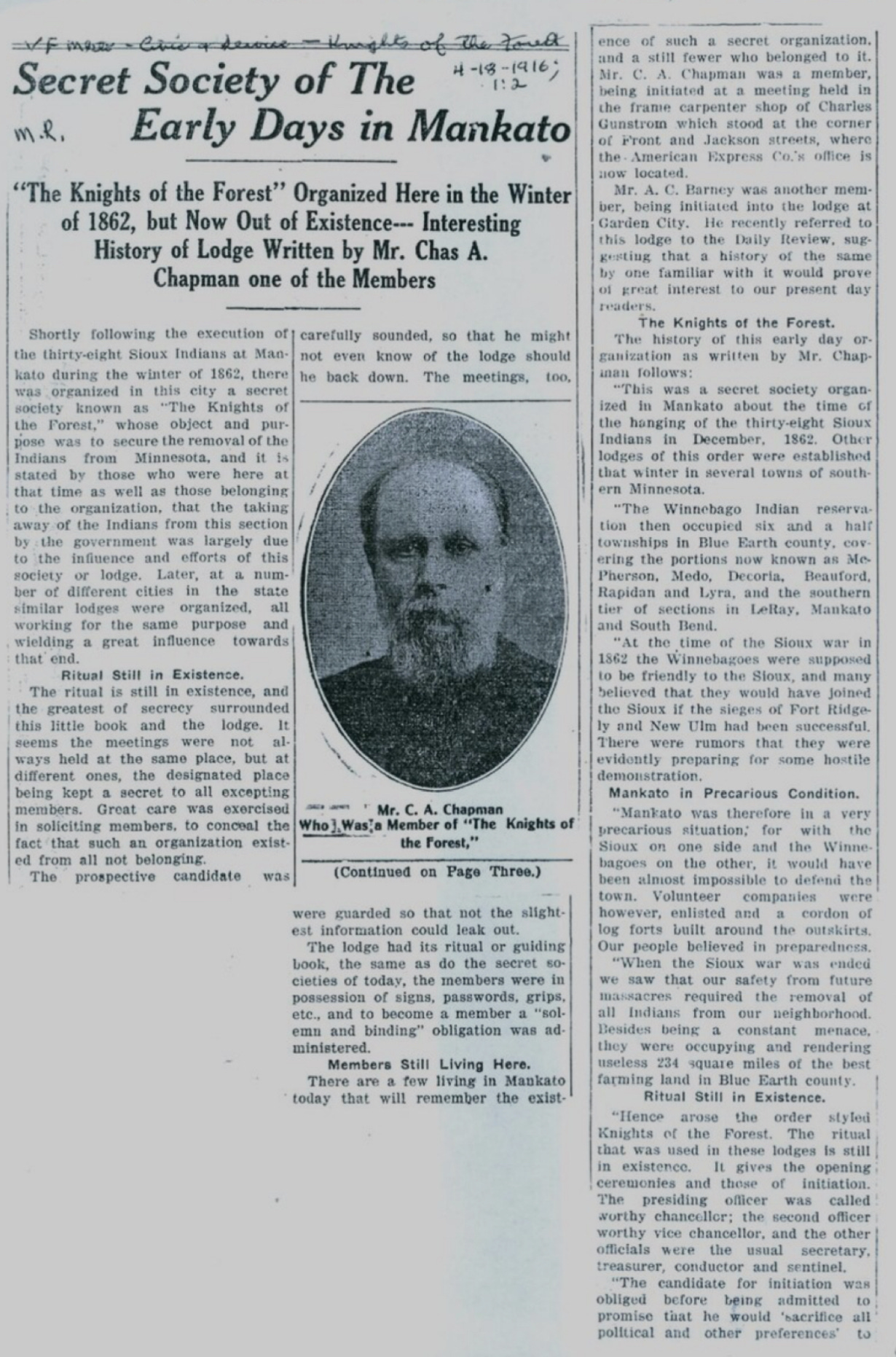

One of those hidden histories is a group many have never heard of: the Knights of the Forest, a white supremacist secret society formed in Mankato, Minnesota during the winter of 1862–63, after the U.S.-Dakota War.

Their racist and extremist mission was terrifyingly clear:

“To banish forever from our beautiful state every Indian who now desecrates our soil.”

It’s funny how they use the term “our soil” since most Minnesota settlers at this time had been in the Minnesota territory for less than 3 decades, whereas the Dakota had been there for countless generations.

These weren’t fringe vigilantes. They were people of society, bankers, judges, land speculators, politicians—basically the establishment. They weaponized fear and resentment and lobbied successfully for the forced removal of all Indigenous people, including the Ho-Chunk/Winnebago, who hadn’t even participated in the war.

They unfortunately succeeded, ousting all Winnebago and Dakota people from the southern part of the state. This is a clear example of eliminationism, which has been done in multiple instances across American history and we see the same methods happening in Gaza today against the Palestinian people.

By the spring of 1863, with the Ho-Chunk and Dakota Expulsion Acts passed through congress, the Ho-Chunk were forcibly removed from their newest home near present-day Blue Earth, Minnesota—a place now famous for the Green Giant canned vegetable brand. The Ho-Chunk/Winnebago were (and still are) expert agriculturalists, yet they were rounded up alongside Dakota prisoners , violently imprisoned, then shipped to what is now Crow Creek, South Dakota. All this was done intentionally with the heavy influence of the powerful members of the Knights of the Forest.

My own Dakota ancestors survived that expulsion and deadly boat ride from Fort Snelling to South Dakota via the Mississippi and Missouri rivers.

This land theft goes deeper:

The Business of Erasure: Half-Breed Scrips

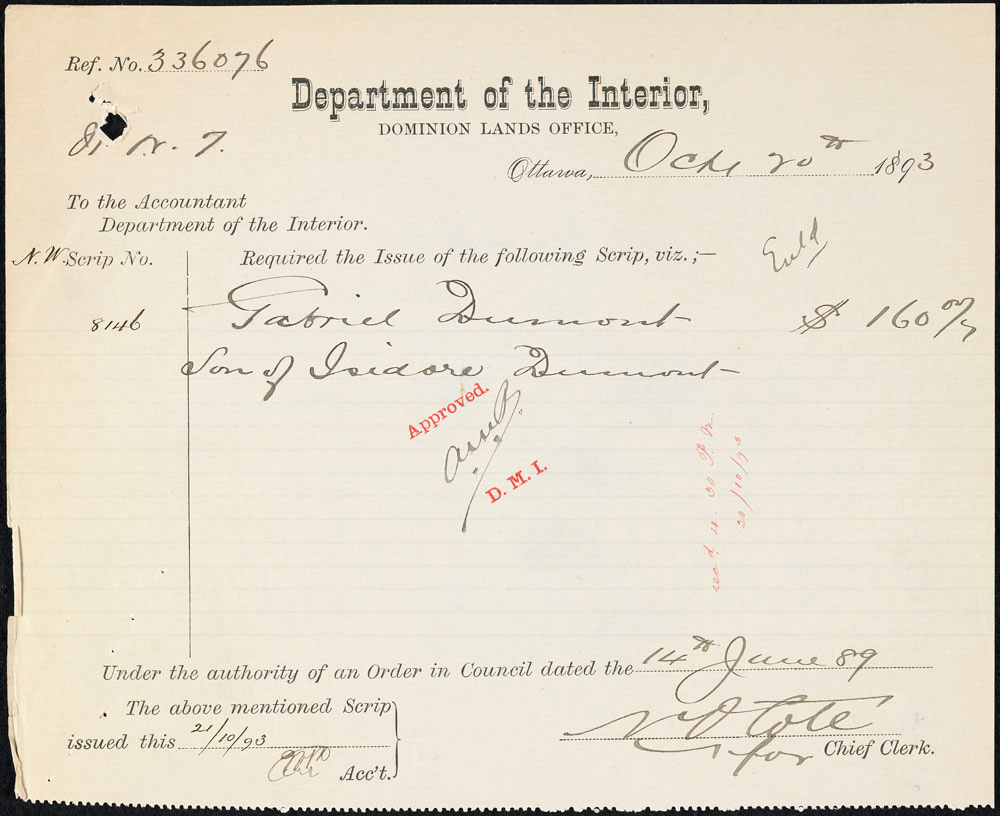

At the same time, another form of legal land theft was underway: half-breed scrips.

Originally introduced in the Treaties of Prairie du Chien (1825–1830), these scrips were certificates supposedly created to grant land to mixed-heritage Dakota and Ojibwe individuals. In reality, they became a tool for wealthy white speculators to snatch up land through manipulation and fraud.

Men like Franklin Steele (read how he swindled Dakota prisoners here), T.B. Walker (of the Walker Art Center), Norman Kittson, and Henry Mower Rice built their fortunes this way, claiming timberlands, riverways, farmland, and future town sites that were once Dakota and Ojibwe homelands. They used these lands to build empires and bases of wealth that are still prominent today. Today, they’re remembered as “founders” and “visionaries.”

But their legacy?

It’s one of broken treaties, erased identities, stolen land, and the severing of Indigenous food systems across the Minnesota landscape.

What does this have to do with Native Food? Everything.

Talking about Indigenous food cannot just be about trends, culinary styles, or romanticized pasts. It’s about truth. It’s about land. It’s about survival.

Before colonization, our people maintained rich, localized food systems. We fished rivers, harvested wild rice, followed bison migrations, gathered medicines, and celebrated seasonal abundance. Food was sacred. Shared. Ceremonial.

Colonization wasn’t just about land—it was about disconnecting us from our knowledge, our ecosystems, and each other. The destruction of our food systems was a deliberate act of erasure.

As an Indigenous chef, I feel this deeply. The work we do through The Sioux Chef, Owamni, and NATIFS isn’t just about serving beautiful plates of food. It’s about reviving systems, relationships, and identities that were violently disrupted.

Every recipe we create, every seed we plant, every community we feed, it’s all part of a greater movement to reclaim what was taken and to carve a new path towards Indigenous Food Sovereignty.

Food Sovereignty is more than just being food secure— it’s about taking the steps to control your own foods systems outside of government control— to protect the environment that is crucial to food systems, and to promote education and training that will last generations.

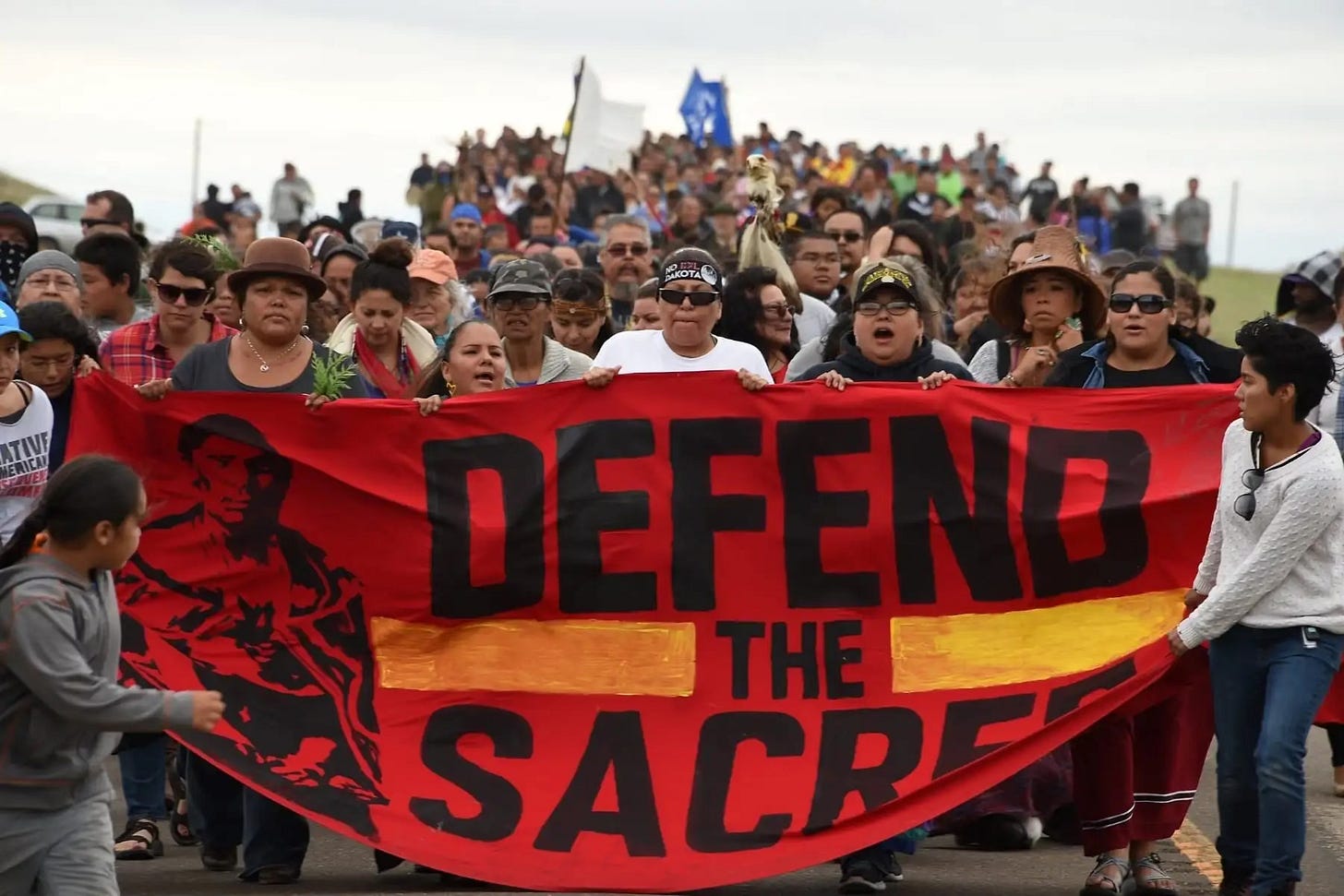

We Are Still Here

What the Knights of the Forest and their allies wanted was total erasure.

What they got was resistance. Survival. And a resurgence they never imagined.

Today, we’re reclaiming our foods, our languages, our lands, and our power.

So the next time you taste wild rice, bison, or a foraged berry grown, harvested, or served by Indigenous hands—remember:

You are tasting a story. A survival. A resistance.

And a future we are writing—together.

We can’t change the past. But we must learn from it.

We owe that to the generations to come.

Wóphila tȟáŋka (“Many Thanks,” in Lakota)

I’ve come a long way from growing up in the rural Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in the colonial state of South Dakota, and all the work I do is about making the right changes for a better future. I just want to see the next generations receive the knowledge and access to grow and evolve our Indigenous Food Systems to great heights— further than I can take it in my lifetime.

Let’s keep feeding each other, telling the truth, and centering our efforts on what matters: community, justice, and humanity.

And to the billionaires and politicians trying to divide us with greed and fear? (besides the obvious ‘Fuck You’):

You can keep shouting into your echo chambers.

We’ll be over here—healing, thriving, and feeding the future.

Skoden…

— Sean Sherman

RECIPE OF THE WEEK (for paid subscribers):

Since it’s Maple Season, I thought this Owamni classic would be fun to share!

Maple + Cedar Baked Tepary Beans

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Sioux Chef by Sean Sherman to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.