F*ck Columbus

An Indigenous People’s Day Recipe for Decolonization

Happy Indigenous Peoples Day!

I actually don’t need to write about Columbus because only an idiot would think Columbus was some kind of American Hero that needs his own holiday. So instead i’ll start with this statement:

“Just stick to f*cking cooking and stay out of politics.”

I’ve lost track of how many times I’ve been told that in the comments under my social media posts.

It’s almost always from brand-new troll accounts with no profile picture, just a digital white sheet. They get apparently triggered when they see a chef talk about non-white history, colonialism, or racial inequality. They want their food to exist in a vacuum so they can enjoy their crispy tacos and blue margaritas stuffed with baby coronas without activating their fragility or white guilt.

Or maybe they’re just Russian bots.

Either way, this work has never been just about cooking. For me, it’s always been about better understanding of our food systems, tracing how they broke, and working to fix them. And yes, it has always been political. Food history shows who holds power, why, who eats and who starves, and whose stories are remembered and whose are erased.

Like my ancestors, I refuse to be erased.

And so should we all.

Cooking, for me, is a tool of resistance. It’s a way of mapping our place on ancestral lands, piecing together our shattered lineages with truth as the glue. Every heirloom seed, every decolonized recipe, every community meal we share is a thread that ties us to our ancestors, our ecosystems, and the hope and health of future generations.

The colonial project was never just about land theft, it was also about food theft, educational theft, cultural theft, and ultimately the theft of self-determination. Colonial systems have erased and continue to erase entire cultural frameworks that sustained people for thousands of years, replacing them with dependency on capitalism, government rations, ultra-processed foods, and so-called “handouts.” And then they shame us for that same dependency.

They handed out violence and racism like candy at a small-town Fourth of July parade.

For me, decolonization starts in the kitchen, and it reaches far beyond that.

But for the fragile internet people who only see recipes coming from BIPOC chefs, I’m happy to oblige.

Here’s my Indigenous Peoples’ Day Recipe for Decolonization.

FEAST for Decolonization

Serves: All of Humanity

Prep Time: 500 years of colonization

Cook Time: Seven Generations

Ingredients:

F — Food Sovereignty

E — Educational Sovereignty

A — Action

S — Solidarity

T — Transformation

Step 1: Food Sovereignty — Regaining the Power to Feed Ourselves

Food sovereignty begins with remembering that food should be a human right. Controlling food is intentional, but food was meant to be shared.

Before colonization, Indigenous nations across Turtle Island—and the world—cultivated, foraged, hunted, fished, and traded within systems of reciprocity. Food wasn’t separate from land or water or gratitude. Our ancestors understood sustainability not as a policy or college coursre but as a way of being.

Our food systems were communal. Everyone played a role—planting seeds, tending crops, harvesting, hunting, fishing, preserving, cooking and teaching the next generations. Ensuring that the community passed along a shared responsibility and deep respect for the earth.

Colonization broke that relationship. It turned land into property and food into a commodity. Today, we’re born into a world where, to eat, you must have money and nutritional access is a privilege. The U.S. government forced Indigenous communities into dependency through rations, commodity foods, and the FDPIR (Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations). Within one generation, Indigenous diets and health were devastated.

Food sovereignty means reversing that damage—rebuilding local control and balance.

The basic steps include:

Environmental protections through land and water conservation led by Indigenous stewards.

Creating demand and support for cultural and regional food producers.

Removing government control from food systems.

Teaching Indigenous education around food production, land management, permaculture, and agriculture.

Investing in food processing facilities to preserve, process, and distribute local foods.

Food sovereignty is ongoing work. It’s a relationship, not a policy. Colonization was built on theft and ownership without respect. Food sovereignty is a return to respect, community, and self-determination.

And it’s a necessary first step toward freedom from systems and governments that never had our best interests—cough, cough, USA.

Step 2: Educational Sovereignty — Unlearning the Colonial Norms

The colonizers didn’t just take the land; they rewrote the textbooks—and they still are doing it.

Indigenous knowledge represents thousands of generations of observation, experimentation, and innovation: agriculture, permaculture, preservation, language, astronomy, medicine, crafting, and science. Yet it’s dismissed as “primitive” until Western academics rebrand it as a “discovery.” Schools still teach that history began with Columbus and that Western civilization saved us all—without acknowledging the genocide, slavery, land theft, and systemic racism that continue to shape our world today.

Educational sovereignty means reclaiming our own curriculum and realizing that knowledge doesn’t need to come through a Eurocentric lens.

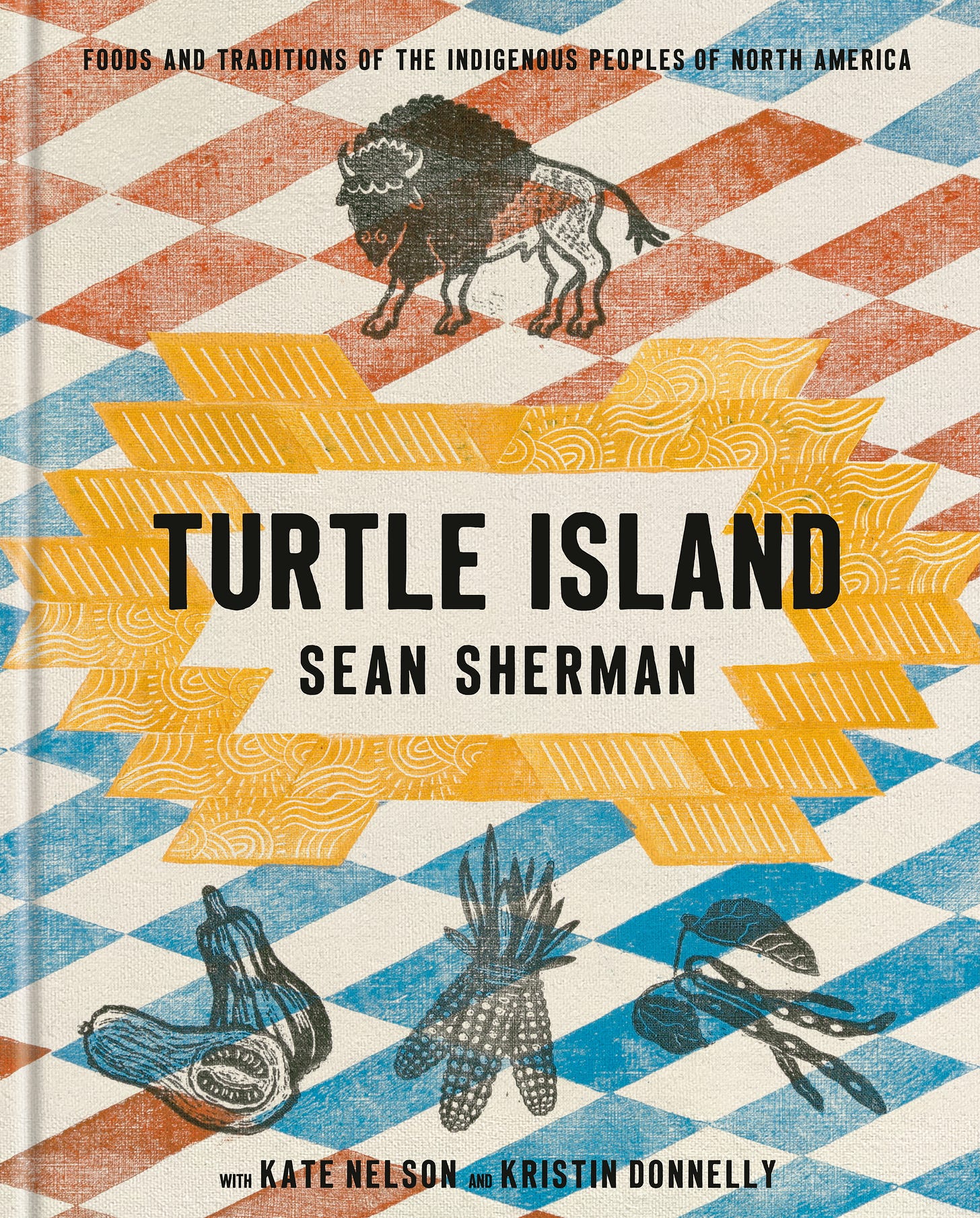

With my soon-to-be-released cookbook, Turtle Island (available 11/11), I hope readers might take time to look past a world built on borders and capitalism to imagine a better way forward—one rooted in a deeper understanding of the past.

Each recipe is a history lesson. Each story is a piece of evidence that we can move the dial toward humanity. Education doesn’t need to be transactional. It can simply teach our youth to be better humans—through a deeper understanding of history, the environment, and the responsibilities that come with knowledge.

When we make foods like smoked duck with wild plum sauce or wild rice with walleye and watercress, we’re learning more than cooking—we’re reconnecting.

Educational sovereignty also means sharing that knowledge. When kids grow up learning where food comes from, who grew it, and whose land it’s from, we start building a generation that can no longer be lied to.

Decolonization begins when we stop asking permission to tell our own stories and control our own narratives.

Step 3: Action — The Act of Making Sh*t Happen

We live in a time when posting something online can feel like activism. But real change requires movement—planting, building, cooking, teaching, organizing. Not just sharing memes or jumping on digital bandwagons to cancel people.

Decolonization is an active verb. It’s something you do with both your mind and your hands.

For me, action has meant building the infrastructure that didn’t exist: creating a nonprofit restaurant with a purpose—to train a workforce, build future leaders, and drive food dollars toward Indigenous producers. But it also means making everyday choices that align with those values: buying from Native producers, supporting community gardens, learning ancestral foodways and ever evolving.

It’s about shifting from consumption and extraction to contribution.

In other words—walk the walk. Real change happens through action, and every day is a good day to start.

Action also means holding governments and officials—local, state, and federal—accountable, demanding policies that restore land, protect water, and ensure that Black, Indigenous, and other marginalized communities are not an afterthought but the foundation of our food systems.

If a politician is against DEI, then they are for homogenization, inequity, and exclusion. Call them out for what they are. Don’t fall for hot-topic catchphrases—demand humanity.

The recipe for change doesn’t work if you leave out the work.

Step 4: Solidarity — Feeding Each Other

Colonialism divides us—and that siloing is also intentional. Separating Indigenous from Black, immigrant from immigrant, poor from poor keeps the status quo intact. The myth of scarcity keeps most of us fighting for crumbs while billionaires feast.

Solidarity means remembering that our struggles are intertwined and that we are stronger together.

Social media and major news outlets profit from division and outrage. It’s easy to share hate on Facebook or Twitter; it makes people feel part of a club. But it doesn’t teach us conflict resolution or empathy. People have stopped having real conversations.

This doesn’t mean participating in bad-faith “debates” with propagandists like Charlie Kirk, who disguise white supremacy as free speech and manipulate young Gen Z audiences with diversionary rhetoric. Solidarity means calling out those systems directly—naming white racial superiority, misogyny, and profit-over-people ideology for what it is.

When we fight for decolonization, we fight for Black farmers, migrant workers, and every community exploited by the same colonial machine. Solidarity can’t be labeled and dismissed as a DEI project or a trend—it’s mutual nourishment. It’s about joining hands and standing up against those who value wealth over humanity.

My partner Mecca Bos has done tremendous work through the BIPOC Foodways Alliance, breaking down cultural barriers through food and storytelling. Their events under the name Immigrant Kitchen celebrates women without restaurants from Palestine, Afghanistan, Mexico, and Black America and have become community feasts of resilience. It feels like being in your auntie’s kitchen, hearing stories and sharing flavors across borders.

We need more spaces like that—where food becomes the bridge instead of the battlefield.

We are the majority. And when we combine our voices and stand together, that’s solidarity in action.

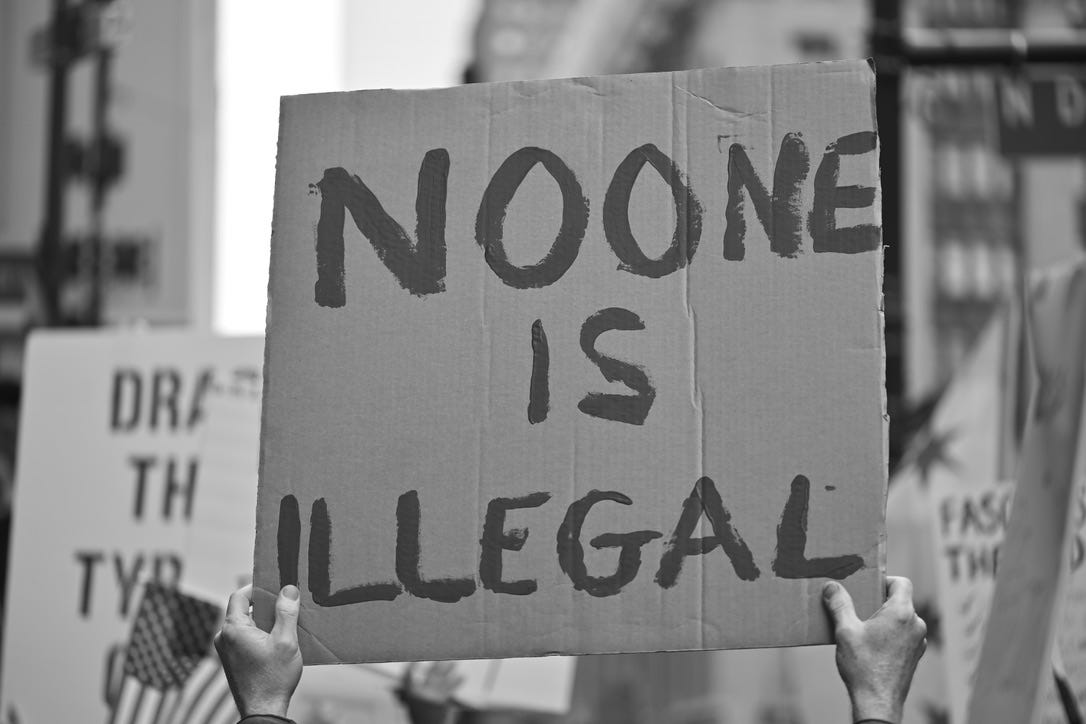

Empires build walls and imaginary lines. Kitchens build connection, memory, and resistance. When we eat together, we remember who we are—and what love and respect can taste like.

Step 5: Transformation — The Real Feast

Transformation begins with the simple act of waking up.

Every day, we’re fed distraction: endless doomscrolling, division, outrage, propaganda—all designed to keep us exhausted and disconnected. The colonial project has evolved; it’s digital now, algorithmic, and wildly profitable.

Transformation means stepping out of that fog. Turning down the noise. Listening to the earth, to elders, to each other. Across the globe, Indigenous peoples hold generations of wisdom on how to live in balance. Food is always at the center of that wisdom.

Transformation also means collective healing. It’s not about one person eating better or feeling enlightened; it’s about changing communal systems that have normalized exploitation. We’ve been taught that struggle is the norm, that success requires competition. But money and borders aren’t real. Food and water are.

Transformation is a process and the outcome of decolonizing ourselves, our actions, our stories, our foods and recreating the senses so we can taste, feel, and imagine humanity again.

Every time we choose balance over profit, connection over consumption, we shift the story of what the world can become—a world that values humanity and earth over the success of petty billionaires.

Transformation is normalization of our actions set in motion. We need decolonized lifestyles, education, food services, and voices to be the new vibe. Our next generations need to see decolonized everything everywhere, but it’s up to us to make that the future reality. If you haven’t already started, then start today.

Conclusion — The Revolution will not be live streamed…

Every time I speak history, someone says, “Stick to cooking.”

Of course I will stick to cooking because cooking is the revolution.

It’s where we remember that we belong to the earth, not the market. It’s where we dismantle systems not with slogans but with sustenance. It’s where we feed resistance, love, and imagination in equal measure.

Food has always been more than survival—it’s been our language, our archive, our medicine, our protest. Every meal prepared with intention becomes an act of repair. Every community dinner, a declaration that we’re still here.

Decolonization doesn’t need another think tank, billionaire savior, or political campaign. It needs people—gardeners, seed savers, cooks, storytellers, teachers—ready to feed each other again.

If colonization was about control through hunger, then decolonization is about freedom through nourishment.

So yeah—I’ll stick to cooking.

Because through food, we can build a world that finally tastes like justice.

And that’s a recipe worth sharing.

Happy Indigenous People’s Day, and F*ck Columbus

*Pre Order Turtle Island Today! Out November 11!

This is all so good. I remember when I was working in higher education in Portland, and teaching faculty how to think about sustainability. One of the faculty, a French professor, said ... you know, that word has no meaning in France. We think about our food as being from the earth where we live, and that's just the way it is. And why would you not take care of that earth where you are growing your food? It's just the way it is.

Your approach providing nourishment from a kitchen stocked with local sustainable food prepared by chefs knowledgeable in human relationships and informed from the past with an eye to the future - my kind of revolution. Glad you are sticking with cooking while essentially transforming politics one meal at a time.